tl;dr — This is a long post, so here’s the gist: Cameras don’t really matter, because they all work basically the same way. What, how, and why you make photographs are more meaningful questions to ask when you’re getting serious about photography.

Grab something, anything—even your smartphone—and make photographs deliberately. A deliberative, contemplative, and reflective approach toward the images you make and share is much more important than the camera. This applies to visual researchers, but I’m pretty sure it applies to most image-making scenarios.

Every so often I get an email or message from someone who writes to ask: “What camera should I buy?”

This is a tricky question to answer, and I usually respond with questions of my own: What are you going to photograph? What do you want your camera to do for you? How much can you reasonably spend? Do you care about having multiple lenses? Do you care about how your camera looks, as an object, in addition to how it sees?

I’ve answered the question of “what camera to buy” enough times that it occurred to me to write a post about it. It’s weird that I even get this question, though; I’m nowhere near a professional photographer, nor do I keep up with gear. If you say “I’m thinking about buying X Camera,” it’s quite likely I’ve zero experience with that camera.

I use cameras to make photographs in the processes of conducting research, and in the processes of living everyday life. That said, I have learned a lot about what I want from photography (and cameras are pretty important to photography), so if reading about what I’ve learned is useful to others, then please to enjoy…

Leveling Up as a Photographer

The folks at DigitalRev recently posted a video that pretty well mirrors my own journey as an amateur photographer. It’s very tongue-in-cheek, and well worth five minutes of your time:

Thankfully, I skipped Level 1; I’ve experienced several of the remaining levels to varying extents, though. For example, I did completely geek out on gear (Level 2) before I became a student of photography (Level 3) and embraced the philosophy that a camera should go with one everywhere (Level 4). I dabbled in the hobbyist phase (Level 5), but became bored by message board arguments and the gear pedants and zealots that thrive there as an invasive species (see Level 1).

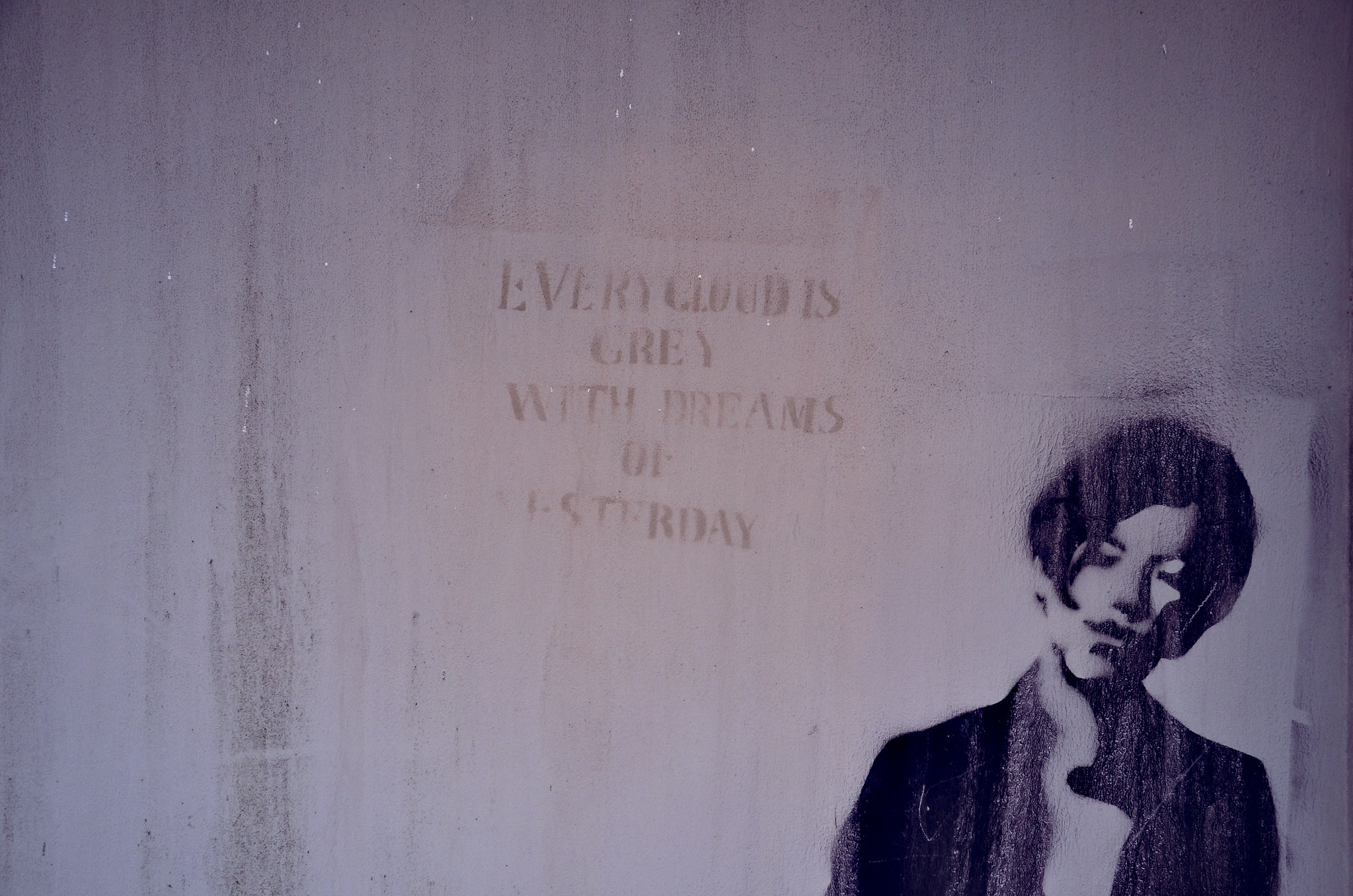

I’m nowhere near an “Online Legend,” Level 6, though I have had a couple of photos make Flickr’s “Explore” page, including this one, which picked up 300 faves and over 20,000 views in a 24 hour period. That was a trip, since I’m lucky to get 1,000 views and 20 faves on any given Flickr photo. Flickr and Instagram mystify me. Images that I think are well-composed and interesting, such as this one, rarely receive much love. DigitalRev’s take on this is spot on, but I digress…

Obviously, I don’t earn my living as a photographer, so I kind of sidestepped Level 7; like many photographers, amateur and professional, I strive to reach Level 8, in my own way. But it takes a while to figure out what you want from photography. It has taken me the better part of the last 3 or 4 years, shooting and editing almost daily, to kind of be happy with what I’m doing and to get what I want from cameras—to get them to see what I see with my eyes and brain. Your mileage will vary, of course.

So, What Is a Camera, Anyway?

It’s a box with a hole in it. Seriously, that’s it. Every camera, ever, is a box with a hole in it. Despite the dizzying array of dials, buttons, and menu options on contemporary digital cameras, the damn things are just boxes with holes in them. I wish someone explained this to me many years ago.

“Wait a second,” you’re thinking. “Surely it’s more complicated than that.” Well, yes, I need to add one other element: material that’s sensitive to light. The predominant light-sensitive material used in photography for 100 or so years was film. Now, our predominant light-sensitive material is a digital sensor.

So, a camera = box (that shuts out light) + hole + light-sensitive material (film or digital sensor). Really and truly, that’s it. Have you ever heard of a pinhole camera? Box, itty-bitty hole, film.

“Wait a second,” you’re thinking once again. “Surely it’s more complicated than this.” It is more complicated, but not much. The things we add to cameras are simply variations on the theme of box, hole, light-sensitive material.

For example, a lens helps us focus the light that comes through the hole and hits the film or sensor. Blades inside the lens help us control the size of the hole, known as aperture. Controlling the size of the hole lets us adjust to different light sources and intensities, and lets us control what’s in focus and what’s out of focus (known as “depth of field”). A shutter gives us control over how long we allow light to shoot through the hole and reach the light-sensitive material. And something called ISO allows us to choose the sensitivity of the light-sensitive material.

Are these things—lens, aperture, shutter, ISO—very complicated? Not really. The first three are all simply improvements upon characteristics of the hole; ISO is an improvement upon the material where light is written. [1]

In sum, the composition of any given photograph involves light passing through a hole into a light-proof box (that is, the light can’t spill out the sides or back) onto film or a digital sensor. You can make a camera with a roll of film and an Altoids can.

If you already knew all this, then I apologize for making you read the last few paragraphs. I write this because I didn’t know this stuff with this kind of clarity until a couple years ago, even though I’d been making photographs since the early 1980s. In fact, it wasn’t until I started seriously shooting film again, in the spring of 2014, that the simplicity of the technical aspects of photography clicked into place for me.

Aperture, Shutter Speed, ISO

This is the stuff to learn, no matter what camera you shoot. What’s the definition of a “user friendly” camera for most people? One that doesn’t make you think about these three things.

But you want to think about these things, because they’re the only things that matter when it comes to the technical side of photography. And once you learn them, they work on any camera. Any camera. Because all cameras work the same way, remember?

Aperture. The aperture is the size of the hole, period. Bigger hole, lower f-stop number; smaller hole, higher f-stop number. F2 means the hole is wide open, while F22 means the hole is really small. Big hole = small focus area. Small hole = everything in focus.

Shutter Speed. Fast shutter speeds freeze movement. Slow shutter speeds blur movement. Want to take a picture of a waterfall? You don’t want to shoot it on automatic mode, with a 1/2000sec shutter speed. Why? Because you’ll get a crappy picture of water frozen in time. Instead, put your camera on the ground or some other stable surface, switch over to “shutter priority mode” and shoot it at 1/2sec or 1 second. Your rocks and trees will be perfectly sharp, but the water will be a smooth, pleasing blur.

ISO. It used to be that you could only control ISO within a very limited range of film sensitivity—between about 50 and 1600 ISO. You selected your ISO when you bought your film, and once that film was in your camera, you were stuck with it. With today’s digital sensors, we can adjust the sensitivity to light (ISO) on the fly, shooting one picture in broad daylight at 100 ISO and the next indoors, in very low light, at 3200 ISO. Because digital cameras are so good with this, you basically almost never need to worry about ISO. It helps to know how it affects your images, though.

Here’s a great little infographic with everything you need to know about how aperture, shutter speed, and ISO affect your shots. This is the stuff to learn.

Shooting Modes

Pretty much any digital camera you can buy nowadays comes with these basic shooting modes:

- Automatic: camera controls aperture, shutter speed, and ISO

- Aperture Priority: you control the aperture (e.g., “I want my background to be blurry, so I’m shooting this at f2”), the camera controls shutter speed and ISO

- Shutter Priority: you control the shutter speed (e.g., “I want the water in this waterfall to be a silky-smooth blur so I’m shooting this with a 1 second exposure”), the camera controls aperture and ISO

- Program Mode: basically a fully automatic mode, but with a little more control (e.g., “I don’t want the flash to fire, but I want the camera to figure out everything else”)

- Manual Mode: fully manual—you choose aperture, shutter speed, and ISO

Most professionals and hobbyists shoot in manual mode, right? Wrong. In my experience, most shoot in aperture or shutter priority mode.

When I’m shooting digital, I’m usually in aperture priority mode. I also have my camera in “Auto ISO” mode. This means that I tell the camera: “shoot between 200 and 3200 ISO, depending on the available light.” (I don’t want it shooting over 3200, because the pictures become grainy in my particular camera—yours may shoot fine up to 6400 or even 12800 ISO).

On the technical side, the only thing I’m thinking about for most everyday shots is the aperture and depth of field—what do I want to get in focus in a given shot? I select the aperture and let the camera figure out shutter speed and ISO. Easy. If I’m shooting something where I either want to freeze movement or show movement, then I’m probably switching over to shutter priority mode.

Put simply, aperture priority and shutter priority modes cover roughly 90% of my digital photography.

If I’m shooting with a flash, or if I’m shooting film, that’s when I’m in manual mode. My film cameras are all fully mechanical—there are no batteries, no electronic components, and so everything is set manually for each exposure.

So, What Camera?

The first thing to consider in any digital camera is whether it has all of the shooting modes I detailed in the previous section. If it meets this very, very basic test, you’re good to go.

The next thing to consider is: fixed lens, or lens system?

I’m not going to delve very far into this at all. But here are some basics:

- “Kit” lenses—those that come bundled with cameras such as the Nikon D3300 in an Amazon deal—are serviceable, but not great.

- Zoom lenses, unless very very expensive, tend to be of lower quality than prime lenses.

- Prime lenses have a fixed focal length—e.g., 50mm.

- Prime lenses typically have a greater range of aperture options, which gives you more control over the creative and aesthetic aspects of your images.

- Prime lenses may be extremely expensive, but they are also sometimes super affordable—Canon and Nikon both make stellar 50mm and 35mm lenses for around $200.

That should suffice. Back to the question: fixed lens or lens system?

A fixed lens camera has one lens that cannot be swapped out for another. If you buy such a camera, you’re stuck with that lens. For many digital cameras, that fixed lens is a zoom.

Lens system cameras allow you to purchase the camera body and lenses separately, giving you lots of flexibility and room for growth over time.

I own several fixed lens cameras (one digital and four film), and two lens system cameras (one digital and one film). They’re all great, and all used to make different kinds of images. My fixed lens cameras are much better looking, as objects, than my lens system cameras, which are big, bulky, and kind of awkward.

Right now, I’d say 95% of my photography happens with a fixed lens camera; I pull out the lens system camera for special situations (photographing written artifacts, shooting portraits, etc.). Don’t make anything of this—it’s a personal preference based on the kinds of things I like to shoot and how I like to shoot right now. It will likely change, so this not an evaluation or endorsement of either approach.

What camera should you buy?

At a minimum, one that has the shooting modes above, and one that will serve you in what you want from photographs now and in the near future (2–4 years or so). If an inexpensive digital camera with a good sensor, full shooting modes, and a competent zoom (or prime) lens will serve you well, go for it. If you want to have the option to add lenses and do specialized kinds of shots, go with a lens system camera.

The stuff that follows is more important, though…

What do you want from your photography?

What do you really want to shoot? Landscapes? Slices of everyday life? Your kids? Archival materials? All of the above?

How you answer these questions will in large measure dictate the kind of camera you buy. But really, no one cares about your camera.

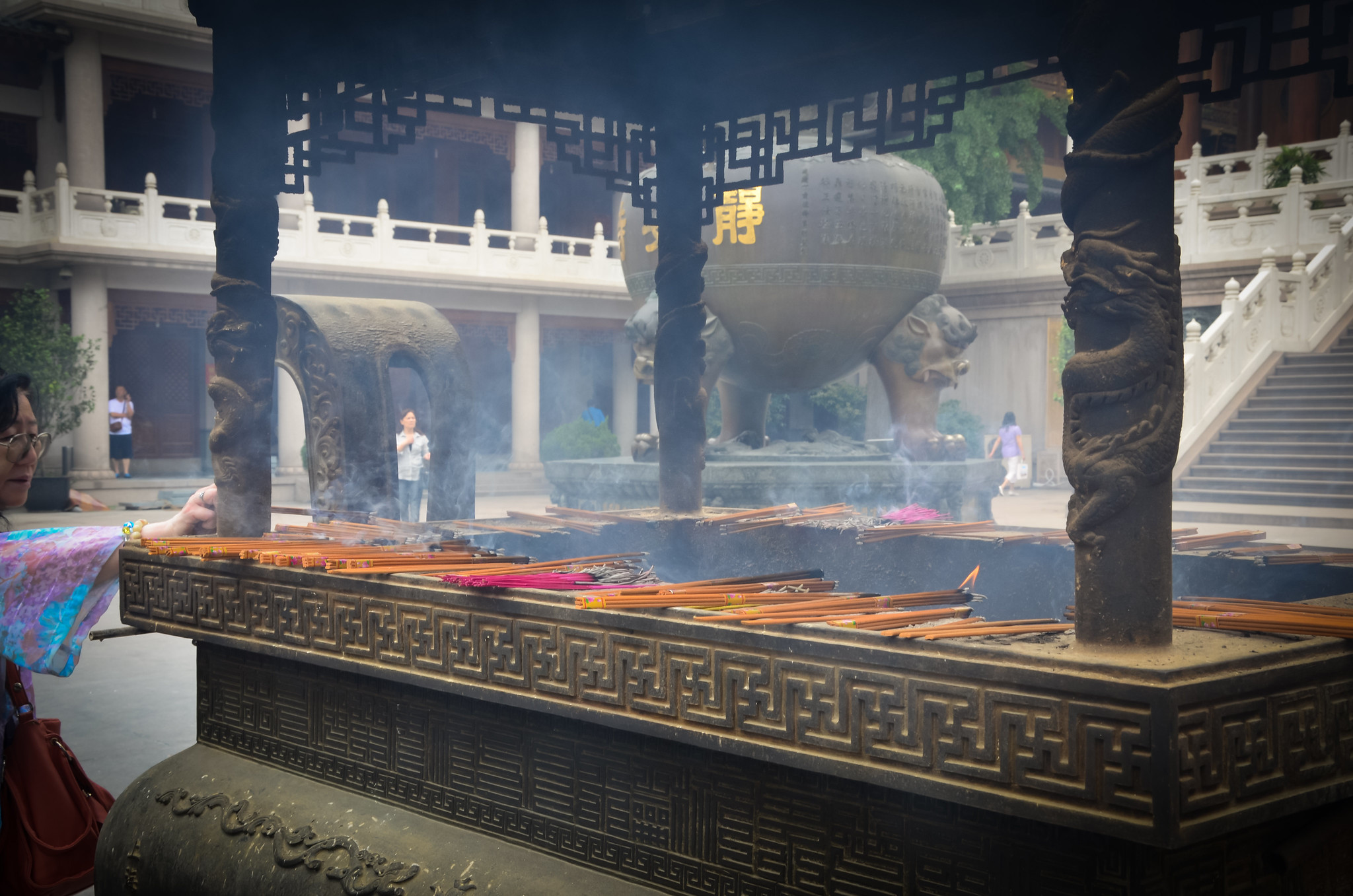

Over the past couple of years, I’ve become most interested in street photography. This is not the art of making shots of streets, but of simply capturing everyday life, unposed, unscripted, as it happens. It’s really hard to do well for a variety of reasons, but my best street photos have emotion and heart, and they make me really happy when they turn out well.

I could shoot my street photos with my digital lens system camera, but it would be… not exactly joyless, but less joyful. Instead I use a small, fixed lens rangefinder camera, either film or digital. I recently finished a research project using only one of these cameras, and it was very satisfying, both while shooting and during processing. The camera fit the project so well.

The thing is, I didn’t know what I wanted from photography until I’d spent a few months shooting every day.

My advice then, is simply this: Grab something, anything—even your smartphone—and make photographs deliberately. A deliberative, contemplative, and reflective approach toward the images you make and share is much more important than the camera. This applies to visual researchers, but I’m pretty sure it applies to most image-making scenarios.

-

BTW, improvements to the box are responsible for most of the complexity we feel are part and parcel of digital cameras. But the fact that a very complex computer now sits inside the box doesn’t really change anything about how cameras work. ↩