In Academic Writing as a Social Practice, Linda Brodkey (1987) argued that composition studies needed a new cultural conception of composing, one that reimagined the tired trope of the alienated and anguished writer who writes alone. In a chapter titled “Picturing Writing,” Brodkey relies heavily on visual metaphors; she passionately argued that we need new pictures of writers and composing practices in their rich, socially situated complexity. She asked readers to re-see writing, to consider alternative viewpoints, and in the process, to break away from popular perceptions of composing, particularly because such perceptions obviate new, different, or even challenging perspectives about writing (58).

More recently, Jody Shipka (2011) draws on Brodkey to suggest that one charge of contemporary composition research is to foreground and make more visible the circulatory processes of composing and textual distribution (38). In response to these and similar exigencies, I compose with photography as one way in which to see writing anew—a method for re-seeing the complexity of composing processes by literally and systematically picturing writers and writing.

As a qualitative researcher focused on the activities, objects, and environments of composing, I conduct ethnographies and case studies of writers in everyday life—from academe and industry to religious practice and social gaming. In these studies, I use traditional fieldwork methods such as semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and artifact collection and analysis. In my early fieldwork, I often used photography and videography as well, mainly as means of augmenting observational fieldnotes and capturing informal talk, gestures, and spatial and material arrangements.

A few years ago, however, I realized that my use of visual fieldwork methods, while beneficial, was also somewhat facile in its execution. I learned that over the last four decades, social scientists have explored the nuances of visual methods in studies of social life (see, for example, Pink, 2007; Spencer, 2011; and Pinney, 2011), of which writing is, of course, an inescapable mediator. The subfields of visual anthropology and visual sociology have enriched my understanding and use of visual methods in fieldwork. These approaches have developed in parallel to our own field’s explorations of visual rhetorics, resulting in complementary empirical perspectives on visuality and visibility.

Writing in the world: a tiny geocache container and scroll for logging visits.

More recently, therefore, I have adapted approaches from visual anthropology and visual sociology to the study of writers and their composing practices and environments. Doing so has resulted in many trials and errors, but the struggle has been rewarding: I have learned to use visual methods to explore, analyze, and present the rich materiality of everyday composing practices, and in the process, to formulate new pictures of writers and writing that may be generative for participants and composition researchers alike. More important, by using visual methods in field studies I have been able to create new forms of material engagement with participants about the role of composing in their learning, work, and play.

While critics such as Susan Sontag (1977) have suggested that photography results in the distancing of photographic subjects from photographers, I have found opposite to be true: Visual methods of fieldwork result in qualitatively different forms of intersubjective understanding between researchers and participants. Composing with photography throughout fieldwork can help researchers of writing move beyond mere tautological illustration; by using visual methods, researchers may document and engage simultaneously.

More important, participants may see their own composing environments, tools, and practices in new ways, from different perspectives. A technique known as photo-elicitation uses fieldwork photographs as pivots for better understanding participant practice. For example, by photographically demonstrating a writer’s well-maintained mise en place, the researcher may help make the familiar strange for a participant, and through discussion, develop new insights about their composing practices.

In a similar way, visual methods may result in presentations of experience that are more hyaline and evocative than traditional forms of reporting. Qualitative data is notoriously dense, and for readers, the mass of fieldwork supporting ethnographies and case studies is often opaque. In addition, traditional methods of collection and representation are necessarily sequential; observational fieldnotes, for example, may miss crucial details of actual practice—movements, tools, arrangements, or cross-talk that may meaningfully mediate composing.

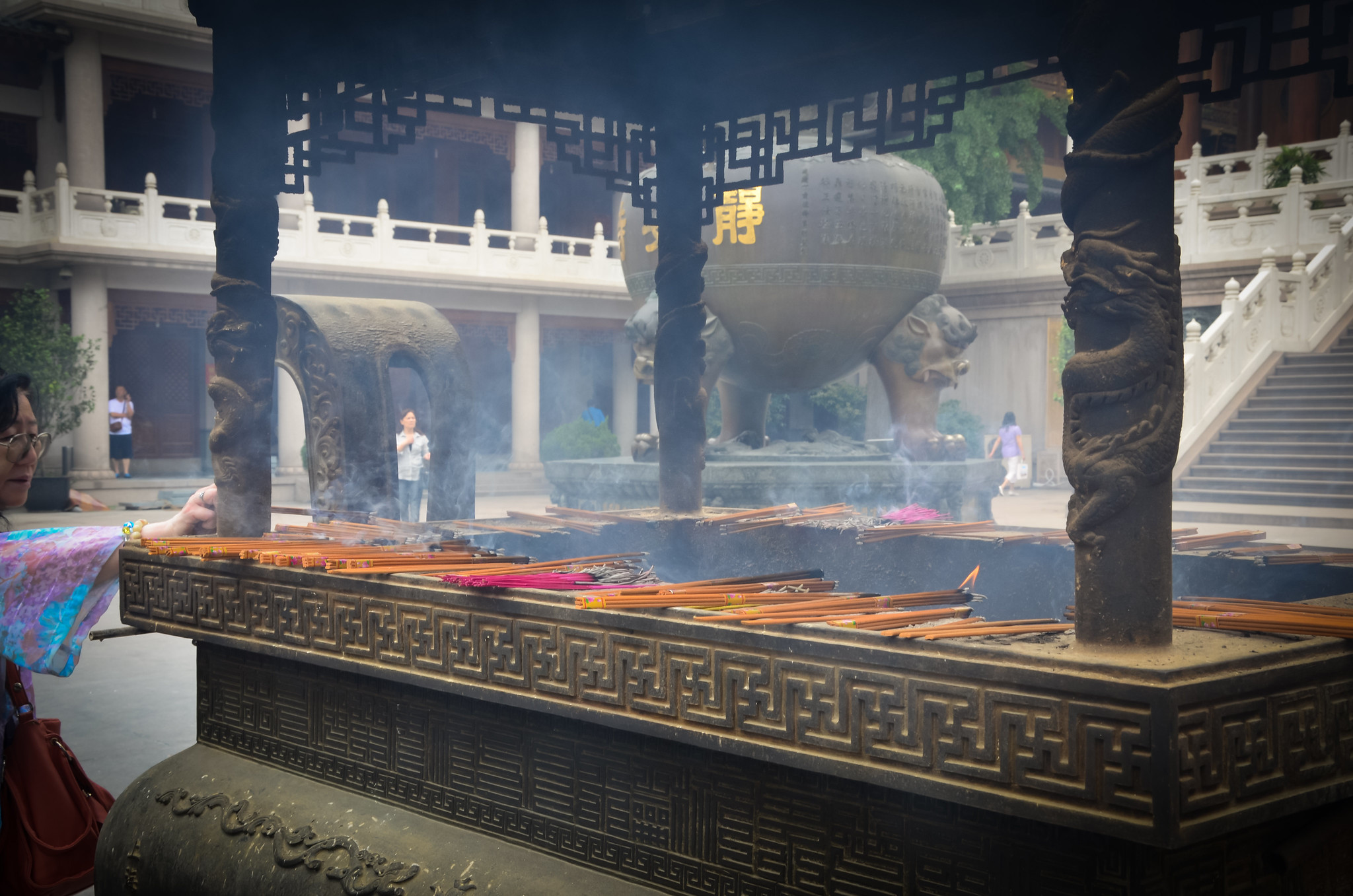

A software studio’s whiteboard is a collaborative space for composing and ideation.

Photographs offer simultaneous renderings of practice, what Flusser (2002) terms surfaces rather than lines. A traditional ethnographer detailing the complex, collaborative work pictured above must transform the simultaneously visible surface of a software studio’s whiteboard into a linear representation of activity. A visual ethnographer, however, can present that visible surface in its full complexity; when coupled with an analytic narrative that details punctuated development, a more hyaline rendering of complex composing practices emerges.

Qualitative research is characteristically ideographic; indeed, visual methods foreground the situated materiality of composing practices. This is a key strength of visual methods as I practice them in studies of writers and writing: the ability to document and collaboratively explore particular systemic contexts and the ways in which artifact assemblages participate in composing processes.

However, in developing new pictures of writers and writing, visual methods have the potential to be nomothetic in the aggregate. Because visual methods may be more hyaline—presenting richer data than traditional methods alone—they carry the potential for fruitful cross-case comparisons of composing practices. Imagine, for a moment, systematically composed and collected photographs of 20,000 first year writers’ typical composing environments and the resulting wealth of both particular (ideographic) and tendential (nomothetic) pictures of writing that might emerge from careful analysis.

Visual methods in empirical studies of writing carry the potential to further develop and realize Brodkey’s argument for re-seeing our object of study, and more important, the people who write. Barthes (1981) argued that “the camera can be an instrument of deep meaning, connecting the scene to the viewer and the viewer to existence” (131). With visual methods, writing researchers can reframe cultural conceptions of where, how, why, and with whom people write in their everyday lives.